BACKGROUND INFORMATION

TRADITIONAL NEIGHBORHOOD DEVELOPMENT: OVERVIEW

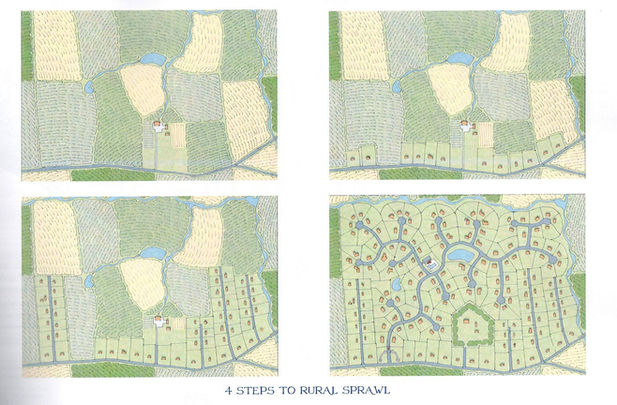

Typical Development Leads to Sprawl

During the latter half of the 20th century, sprawl began to define the American landscape. The automobile, increasingly attainable for more Americans, allowed people to move outside of cities and towns into newly developed subdivisions. Highways allowed for suburban residents to easily reach urban centers for daily needs - at least for a period of time. As suburban development continued, and as commercial businesses dominated the frontage of the highways, road congestion and traffic incidents became a recurring problem in America’s suburbs. Widened highways and new bypass roads provided temporary relief from these issues, but also induced new development - and ultimately more traffic - while compromising the natural beauty of the lands they bisected.

Other than the traffic problems created, sprawl also robbed communities of their “sense of place.” By separating different types of housing, commercial uses and civic spaces into their own pods along the highway, the resulting development had little character and didn’t properly reflect local identity.

A Solution

In the early 1980s, a group of planners, architects, and academics set out to solve the mounting problems of increased sprawl. The answer to these new issues, they discovered, was actually found in the past. Their model - known as “Traditional Neighborhood Development” (also called “New Urbanism”) - is based on how towns and cities were planned prior to the mid-twentieth century. Before the automobile, communities were planned around the ability to reach essential services by foot. When growth demanded it, new neighborhoods were platted out on grid patterns. Traffic was distributed amongst local streets rather than concentrated on collector roads. Neighborhood main streets could be reached by foot from residential areas, providing residents convenient access to shops, civic spaces, restaurants, and workplaces without the need to leave the neighborhood. Main streets were often mixed-use, giving residents ultimate ease of access to commercial services, while also giving the main street vibrancy and local identity.

By applying these principles to new development, communities could meet new housing demand while mitigating the traffic and land use issues caused by typical sprawl.

TRADITIONAL NEIGHBORHOOD DEVELOPMENTS IN BOTETOURT COUNTY

Protecting our natural resources while planning for smart growth

Beginning in the early 2000s, Botetourt County began an effort to restrict sprawl and encourage smart land use. The county incorporated Traditional Neighborhood Development (TND) zoning into the county code, enabling new communities based on the principles of walkability and livability.

In a 2010 update to the county comprehensive plan, Botetourt County identified ideal sites for future mixed use developments. A “Regional Mixed Use” location was identified at the Gateway Crossing area of the county (also known as the Exit 150 area). This site is meant to serve to regional travelers and local commuters on the I-81 corridor. A “Town Edge Mixed Use” location was identified on the southern edge of Fincastle. This designation is meant to allow for the responsible residential growth of Fincastle, while protecting the existing mixed-use areas within town limits.

The county also identified two “Community Mixed Use” locations, meant to bring Traditional Neighborhood Developments to existing higher-density residential areas. These mixed use developments should bring new business and civic space for current residents while offering new housing options for the area. One of these targets, located north of I-81 on Route 220, became the successful Daleville Town Center. A second target area, south of I-81 on Alt. 220, is located at the Murray Cider Co. property.

ABOUT THE MURRAY CIDER PROPERTY

Murray Cider Co. History

Early in the 20th century, apple orchards dominated the foothills of Read and Coyner Mountains. In 1929, a severe hailstorm ravaged the area, rendering most of the crop unfit for sale. That’s when Walter Kent Murray decided to turn lemons into lemonade - or, more literally, bruised apples into cider.

In the following decades, Murray Cider Co. became a Botetourt County icon; its towering silo visible to the thousands of daily travelers on Cloverdale Road. As orders for Murray Cider soared, hand-cranked presses were replaced by larger industrial ones. At its peak, Murray Cider Co. produced more than 1,000,000 gallons in a year for buyers nationwide. Despite the company’s growth, it stayed true to its family roots - being run by Murray Family members over the entire life of the company. It also never compromised on quality - refusing cheap concentrates for real apples, and continuing to use distinctive glass jugs - long after their national competitors moved to plastic.

By the 2010s, the environment around Murray Cider Co. had changed significantly. The sprawling orchards of the area had become sprawling suburbs, forcing the Murrays to purchase apples from further away - ultimately from other states. Price hikes and dwindling supply became recurring issues, forcing the company to scale back production. By 2015, Murray Cider Co. halted production all together.

About the Property

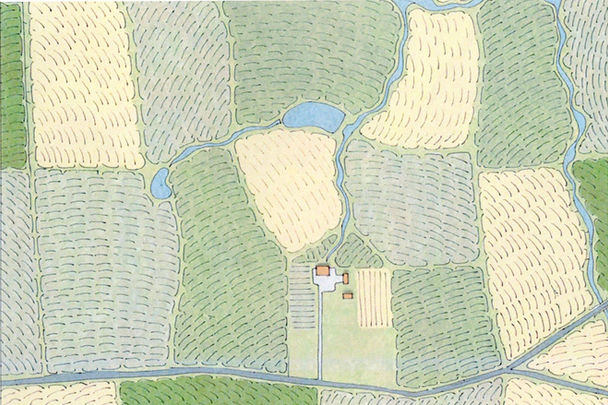

The Murray Cider Co. property is an 89 acre parcel on Alt. US 220 in Botetourt County. It offers gently rolling slopes, a large “sky pond” near the top of the property, and stunning mountain views.

Surrounding the Property

-

East Park manufacturing campus to the north

-

Peachtree subdivision and Jeter Farm to the east

-

Bonsack and US 460 to the south

-

East Botetourt & Orchard Hills subdivisions, The Orchards apartment complex, and patio home developments to the west across Alt 220

A Traditional Neighborhood Development on the Murray Cider Co. Site

We agree with Botetourt County’s identification of this site as an ideal location for a Traditional Neighborhood Development. The medium and high-density residential areas, popular civic spaces, and large office and manufacturing facilities that surround the property would benefit from a well-planned neighborhood center. The property also acts as a gateway to Botetourt County on Alt 220 N. A beautiful community at this location can offer residents and travelers alike a welcoming entrance into Botetourt County.